Index by combination using Pascal’s Triangle. How to invent Pascal’s Triangle. Combinations with repetition index.

Problem statement:

Some time ago I had a requirement to get index/location for a given combination out of a list of given “combinations with repetition” sequence.

For example if we have n = 3 (number of things to choose from) and r = 3 (we choose r of them) then we have 10 combinations total, which means we have the following table:

[1, 1, 1] # index = 1

[1, 1, 2]

[1, 1, 3]

[1, 2, 2]

[1, 2, 3]

[1, 3, 3]

[2, 2, 2] # index = 7

[2, 2, 3]

[2, 3, 3]

[3, 3, 3]

Let’s say I’m interested in combination [2, 2, 2] so looking at table above we can tell it’s index is 7 (starting from 1). That was easy, because we can just use brute force and iterate over all possible combinations in this list until currently iterated combination matches with the one we are interested in. But what if we have n =10, r=10 combinations set?

According to combinations with repetition formula:

at worst case we need to see a list of 92378 combinations. Of course we can generate all these combinations and compare with combination we want to find index of. But it is extremely inefficient and even unreal if we have high n and r values (let’s say n=20 and r=20).

So the question is how to find combination’s index (in context of combinations with repetition) just by knowing n, r and combination itself.

Here is my investigation and a visual approach to this problem:

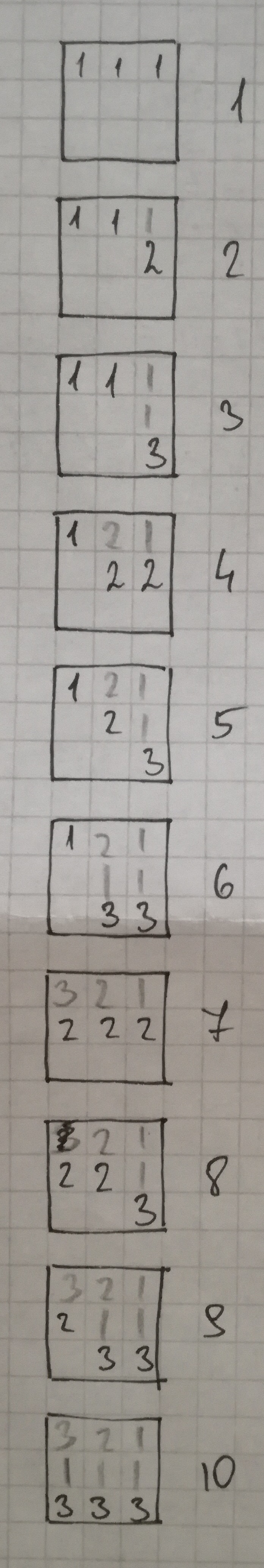

At first I tried to understand how combinations work and how sequence is produced. Here is for example how n=3, r=3 is progressing:

Fig. 1. Here we have all states of let’s call it a “combinations box”. Each box contains state. Each state is a combination in that combinations box. Combination is in black color, cost of the cell/brick/item movement is in gray (cost is explained below). There are 10 possible states.

If we think of the bricks/items movement above in terms of cost we will see that it is cheapest for the right-most item to move down and it is more expensive for the items located to the left and it’s most expensive to move down for the left-most item (because it always waits until all preceding items moved first).

For example 3rd item (right-most) is moving down effortlessly (step 2 and 3 of Fig. 1.). The price is 1 for each movement down.

Now to move middle item down (as you can see it moved 1 position down at step 4) we first had to move rightmost (3rd) item 2 positions down (look at step 2 and 3). So the cost of movement 1 position down for the middle (2nd) item in this case was 2.

Now if you look at step 6 for example, you will see that second movement down of the 2nd (middle) item costs 1 (not 2 like in first movement case at step 4). This is because right-most item could move only 1 brick down (because in combinations with repetition any item on the right is >= item on the left (it must be at the same level or below), so for example we cannot have combination such as [1,2,1] or [2,1,2] etc., only ascending order is allowed).

So for example, according to what we discussed above, the total price is 0 at step 1 (no movement was taken)

The total price for step 7 is 6 because:

- it was necessary to make 3 movements to shift left-most item down from where it was (3 because it was 2 shifts down for the right-most item and 1 shift down for the middle one so 3 in total)

- it was necessary to make 2 movements to shift middle item down (because we first needed to move right-most item 2 positions down to “allow” middle item to move down).

- and right-most item adds 1 unit of cost as well because it is shifted 1 position down to keep ascending order of the combination

So basically combination’s index is its total cost in that table (cost of preceding movements, gray color values in Fig. 1.). If we want to start from index 1, we just add 1 to total cost.

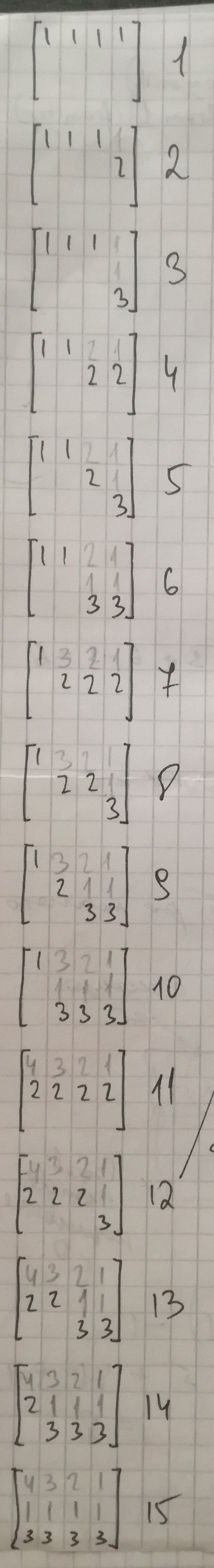

Let’s see another example, n=3, r=4:

Fig. 2.

I’m sure you can figure out the pattern on how to fill those costs. Here is an algorithm in a nutshell. It goes like this. You look at particular brick/item/cell and calculate its cost by adding up all costs in preceding column’s cells (excluding bottom-most cell) like this -> look at the cell on the right (neighbour) on the same level and go down while level is < bottommost level, accumulating costs sum.

For example at step 10 you can see that 2nd cell on the left of first row has cost 3 and it is calculated by looking at sum of costs (gray color values) of its neighbor column on the right -> (cost = 2) + down (cost = 1) -> 3. Same for all bricks/items/cells. And as we discussed, our base case - rightmost column’s cell movement cost is simply 1.

Here are some more examples:

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.1.

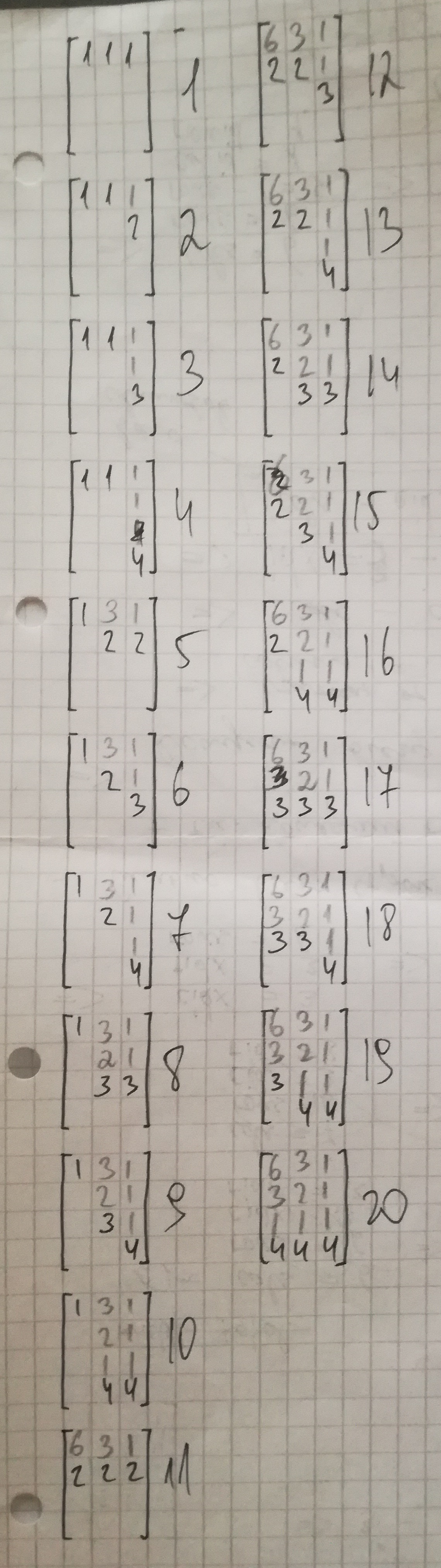

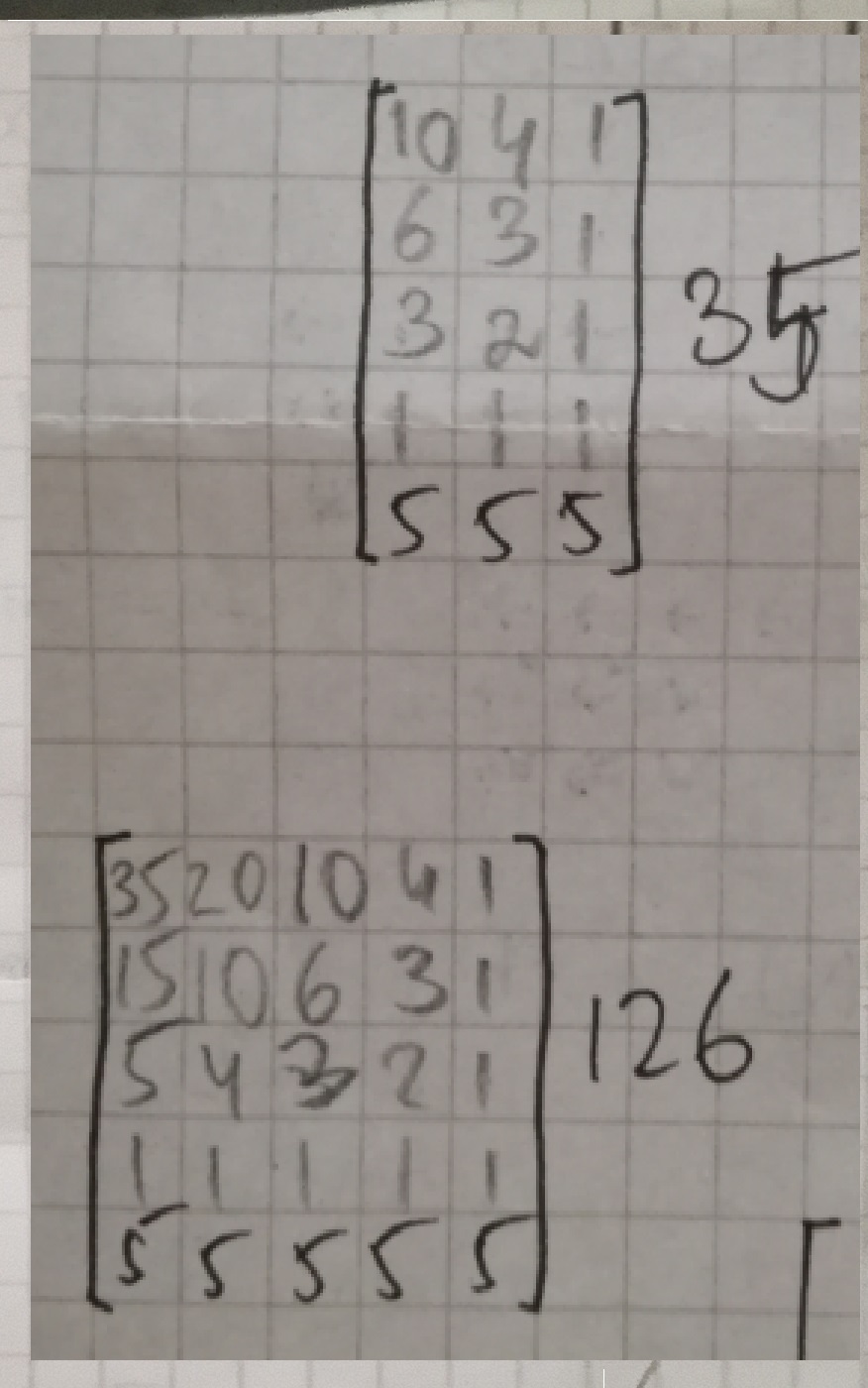

And now we can try a more complex example:

Fig. 4.

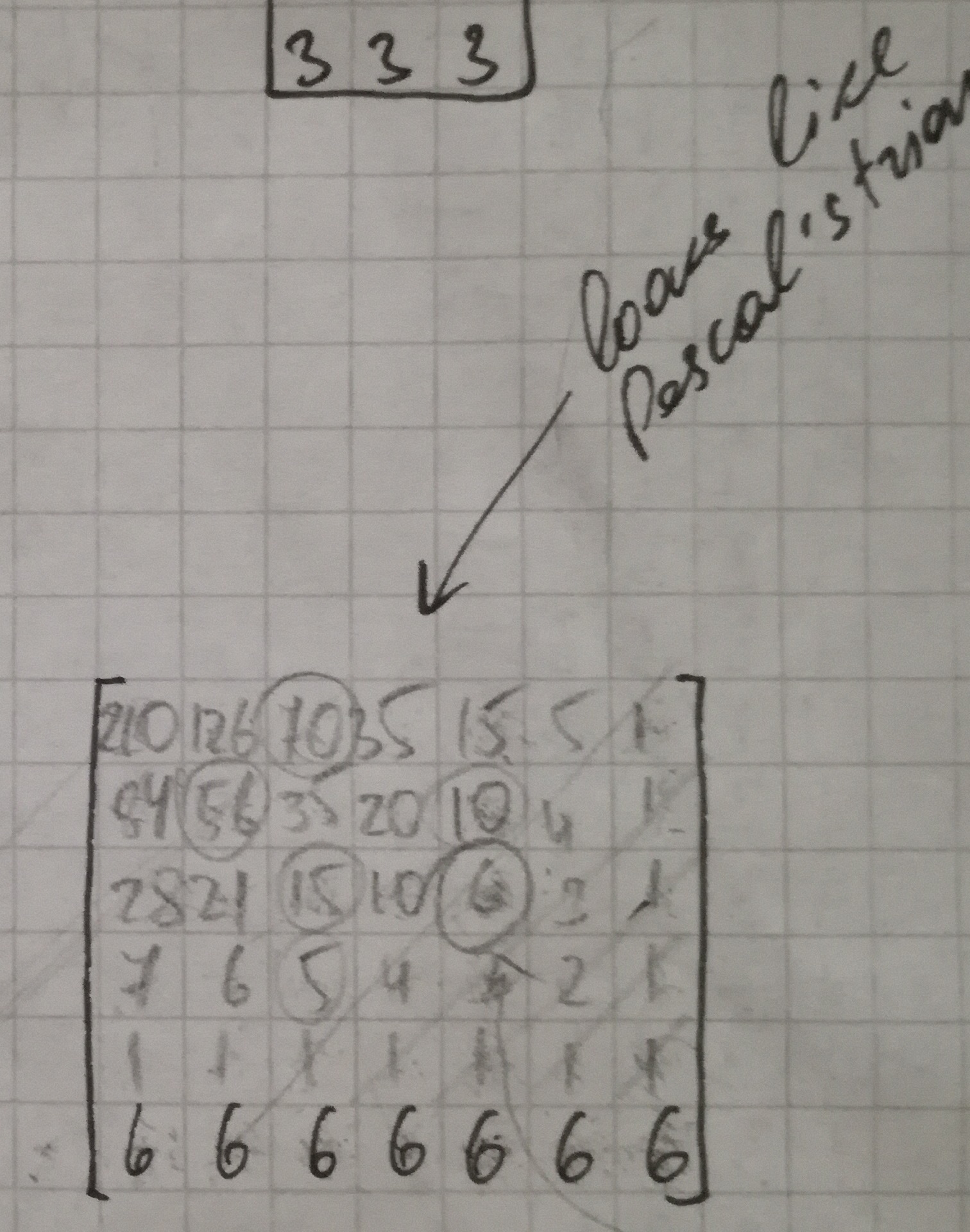

Here I’m just calculating costs for all the movements to end up with bricks positioned at last combination, which is [6,6,6,6,6,6,6].

Now look at these numbers, they are interesting and there is a lot of beautiful correlations between these costs. I clearly saw some interesting patterns. It made me curious about what we are dealing with here. So I tried to google this for example: “6 10 15 21 28” and found things like “Triangular number”, “Tetrahedral number”, “Perfect Power” and also “Pascal’s triangle” which is EXACTLY what you see as costs in the bricks above. We invented a bicycle. Amazing! :D

Pascal’s Triangle discovery was important because now I could for example create a lookup table for all these costs and just add them up to get index of any combination! It turns out it is very easy to generate Pascal’s triangle for any amount of rows. Also you can find cost of any specific brick by nCr formula (look for details here: http://www.mathsisfun.com/pascals-triangle.html)

So let’s say we have n=6, r=7 and we want to get index of [2,2,3,3,4,4,5]

To do so we need to calculate and sum up costs of all bricks above occupied positions. So from left to right it will be (210) + (126) + (70 + 35) + (35 + 20) + (15 + 10 + 6) + (5 + 4 + 3) + (1 + 1 + 1 + 1) = 543. So index will be 543 + 1 = 544 (to get index we add +1 because 1st combination’s cost is 0). (see Fig. 4.)

Again we know cost of each brick simply by looking at Pascal’s triangle (which then we need to generate first) or by using rCn formula (which ironically also may use Pascal’s triangle to calculate it’s value). All we need is a “coordinate” of the brick we want inside Pascal’s triangle.

Here is full implementation in Java:

package my.package;

import java.util.ArrayList;

import java.util.Arrays;

public class CombinationsWithoutRepetition

{

private static final int MAX_TRIANGLE_LEVELS = 50;

private final long[][] _cr = new long[MAX_TRIANGLE_LEVELS][MAX_TRIANGLE_LEVELS];

public CombinationsWithoutRepetition()

{

for (int i = 0; i < MAX_TRIANGLE_LEVELS; i++) {

Arrays.fill(_cr[i], -1);

}

}

/**

* Get combination index by given (actual) combination

*

* @param n (number of things to choose from)

* @param r (we choose r of those things)

* @param numericCombination

* @return

*/

public long getCombinationIndex(int n, int r, int[] numericCombination)

{

long sum = 0;

for (int colIdx = 0; colIdx < numericCombination.length; colIdx++) {

int maxRowIdx = numericCombination[colIdx] - 1;

for (int rowIdx = 0; rowIdx < maxRowIdx; rowIdx++) {

sum += _getCellValue(n, r, rowIdx, colIdx);

}

}

sum++;

return sum;

}

/**

* Get specified cell value out of Pascal Triangle's grid

*

* @param rows

* @param cols

* @param rowIdx

* @param colIdx

* @return

*/

private long _getCellValue(int rows, int cols, int rowIdx, int colIdx)

{

// showing explicitly how level is calculated

int pascalTriangleLevel = (cols - 1 - colIdx) + (rows - 2 - rowIdx);

// explicitly showing how index at given level is calculated

int idxAtPascalTriangleLevel = (rows - 1) - rowIdx - 1;

// get cell-value by given "coordinates" within Pascal's triangle grid

long cellValue = _comb(pascalTriangleLevel, idxAtPascalTriangleLevel);

return cellValue;

}

/**

* This method is based on:

* https://www.quora.com/What-are-some-efficient-algorithms-to-compute-nCr-in-Java

* P.S. this is a highly technical implementation.

* We could use simple Pascal triangle generation algorithm instead.

*/

private long _comb(int n, int r)

{

if (_cr[n][r] != -1) {

return _cr[n][r];

}

if (r == 0 || n == r) {

return 1;

}

long ans = _comb(n - 1, r) + _comb(n - 1, r - 1);

return _cr[n][r] = ans;

}

/**

* Prepares combination to be used with this class

*

* @param combination Array of combination values as strings

* @return int array of sorted combination values

*/

public int[] prepareCombination(ArrayList<Integer> combination)

{

int[] numericCombination = new int[combination.size()];

for (int i = 0; i < combination.size(); i++) {

Integer val = combination.get(i);

numericCombination[i] = val + 2;

}

Arrays.sort(numericCombination);

return numericCombination;

}

/**

* Binary-search combination by given index

*

* @param n

* @param r

* @param targetCombIdx

* @return

*/

public int[] getCombinationByIndex(int n, int r, long targetCombIdx)

{

int[] testComb = new int[r];

int lowerBound = 0;

for (int i = 0; i < r; i++) {

int upperBound = n;

while (lowerBound <= upperBound) {

int mid = lowerBound + (upperBound - lowerBound) / 2;

for (int j = i; j < r; j++) {

testComb[j] = mid;

}

long curCombIdx = getCombinationIndex(n, r, testComb);

if (curCombIdx < targetCombIdx) {

lowerBound = mid + 1;

} else if (curCombIdx > targetCombIdx) {

upperBound = mid - 1;

lowerBound = upperBound;

} else {

return testComb;

}

}

}

return null;

}

}

// usage example:

//CombinationsWithoutRepetition c = new CombinationsWithoutRepetition();

//System.out.println(c.getCombinationIndex(3, 3, new int[]{1,2,3})); // n = 3; r = 3; combination = [1,2,3]

//int[] comb = c.getCombinationByIndex(3, 3, 8); // n = 3; r = 3; combination index = 8

//System.out.println(Arrays.toString(comb));

As soon as Pascal’s lookup table (_cr) is filled, algorithm works pretty fast.

In this class I also made a handy method to perform reverse operation which returns combination by given index (make sure though Pascal’s triangle you use is big enough – see MAX_TRIANGLE_LEVELS constant). Very useful in case you want to “unpack” any index.

I’m sure there are more efficient and optimal ways to do what I described here (some nice formula in statistics), but unfortunately I couldn’t find it so I had to investigate everything myself. But after all it was a very interesting journey! Hopefully it will be useful to you as well!

Cheers!